Many of us have heard, by now, that 90% of start-ups fail. Despite the uneasy statistics, passionate entrepreneurs may often ignore the signs that failure is imminent.

After all, how can disaster be around the corner when you have seized upon a revolutionary, disruptive idea that nobody has thought of; or, when major investors and venture capitalists (VCs) have poured mountains of cash into your start-up; or when you forecast that millions of users demand your product?

The feeling of achievement can often mask the harsh reality. Many companies will come to the realisation that maybe their products weren’t such a big hit, or that they have burnt too much cash on the beautifully designed office space.

Initial success can often drive leaders to be complacent, or lose their bearing on where the business should be heading — a problem Daniel Steenerson, founder of Disability Insurance Services, calls the “middle mile”. Let’s look at some of the often overlooked stories of companies that didn’t make it past this crucial stage of business growth.

#1 Alikolo – Ignorance is bliss

Sometimes being passionate is not enough. This was what happened to Alikolo, a start-up founded by an inexperienced Indonesian graduate in Medan.

Danny Taniwan aspired to become a tech entrepreneur after he witnessed the success of Jack Ma’s Alibaba.

Naming his company after his inspiration, he set out on his entrepreneurial journey with the help of two angel investors. At the time, Taniwan did not even know that he was going up against Tokopedia, Indonesia’s largest online marketplace.

Despite having a poor grasp of the endeavour, he was undertaking, Taniwan’s Alikolo made steady progress as an e-commerce website. This was partly because his company offered free shipping of goods to lure in customers.

He soon found out that this strategy was financially unsustainable. Discontinuing free shipping, however, took away his only competitive advantage – and sales started to plummet.

These troubles were exacerbated by the fact that his investors also had little experience in running an online business. As his company began to fail, Taniwan started to see his mistakes only when it was too late.

An unsustainable strategy, huge gaps in assessing market needs, and ignorance of his competitors drove the business to the ground. He had to face the agony of having his competence be questioned by VCs.

Taniwan was lucky to have ended his journey in 2015 without being in debt. In hindsight, he confessed that he should have sought the help of an experienced cofounder who would have been able to alert him to potential red flags in his strategy.

#2 Research In Motion – Falling behind in innovation

Ideas play an important role in getting a business up and running, but the role of ideas for keeping a business in motion is often overlooked.

Some of the most notable businesses in recent times, like Twitter and YouTube, survived troubling times by conceiving drastic and innovative pivots.

Twitter began as an unimpressive podcast networking website, while YouTube started as a failing video dating site, before going back to the drawing board.

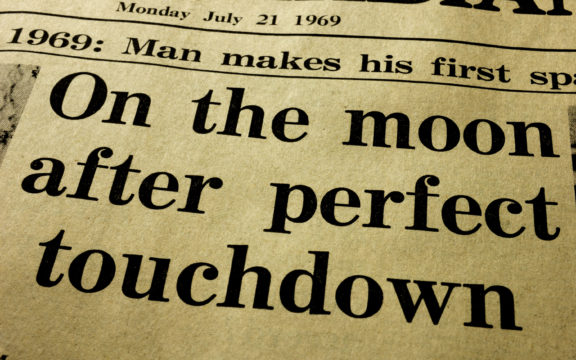

Some companies didn’t make the cut. Research in Motion (RIM), the company that made BlackBerry lose out in the arms race of innovation, began with a simple but powerful idea that won over many customers in the beginning. The technology they developed enabled users to push emails from their handheld devices.

Things changed when others saw the usefulness of that idea and began developing alternatives. The world welcomed the era of smartphones – a device that could do so much more.

BlackBerry devices began to lose their initial appeal, but the company was slow to come up with new or better ideas to outdo rival technologies. RIM fell from being a market leader to almost complete obsolescence.

Creating something that few were capable of – helped to kick-start a stellar beginning.

Complacency over its initial success meant that nothing new or impressive ever came out of the company after years in operation, allowing competing products to beat it.

#3 Sidecar – Waddling in obscurity

Beating competitors in innovation, despite being crucial in today’s technology-driven environment, may not always guarantee success either. SideCar learnt this when they were ultimately defeated by Uber.

SideCar launched in 2012 and became the first true “ride sharing” app, connecting its users to private vehicle drivers. In the business, SideCar clearly had the better technology.

It introduced features that were ahead of its time, outstripping Uber in the innovation department.

As CEO Sunil Paul remarked, the product caught on well and customers loved it. Putting so much effort into innovation, SideCar should have been a success, but they soon faced the realities of running a business.

For the company to survive, the primary concern had to be drawing in as many customers, and dominating the market share.

Uber nailed these down with an efficient sales and marketing team, putting forth their product in a highly visible manner. Uber’s more aggressive push for wider brand visibility meant that more potential customers became acquainted with the product.

They expanded their services at a more rapid pace, enabling customers from all over the world to hail a ride. Having more features than Uber probably made SideCar unappealing to new users who found them unnecessary.

SideCar was beaten by its competitors as it received limited attention from the market. It became too side-tracked on upgrading the product with little regard for what customers wanted.

In 2015, Sunil posted a letter bidding farewell, as the company’s assets were acquired by General Motors.

#4 Talentpad – Misapprehending the market

One of the most common and perhaps most devastating causes of start-up failure is realising that people don’t really need your product.

Equipped with awesome ideas and a passionate team, founders can often be overconfident in how well their company can overhaul the industry.

Founders will often realise that the market is more complex than they first thought. This can often lead to serious introspection about the feasibility of their “revolutionary” idea.

The CEO of TalentPad, Mayank Jain, faced this problem. TalentPad, based in India, was a company aimed at truly optimising the hiring process.

Selecting a suitable person for a job is difficult and inefficient. HR officers must sift through piles of resumes to find the right candidate.

TalentPad would change that. Through state-of-the-art algorithms, it would automatically match an applicant’s experiences and qualifications with suitable job opportunities. This brilliant idea would target the recruitment market worth around US$1bil.

As Jain ventured further into his business, his plans for scaling hit a major roadblock when he discovered that the market was more complex than it seemed.

He found that his product was only suited to the recruitment of junior and mid-level employees. These problems were coupled with the complexity of identifying desirable traits across hundreds of industries, from IT to banking.

This made the algorithms ineffective in practice. Clients were better-served by sites devoted to particular industries.

Combined, these difficulties muddled the scalability of the product. Only a small pool of potential customers were interested in their premise.

The company was left with the choice of either shutting down or completely overhauling their business. It shut down in 2015, less than a year after receiving its seed funding.

#5 Rewardme – Overly aggressive expansion

There is tremendous pressure for companies to be unicorns – small start-ups with the potential to bring billions in return. This drives companies to expand quickly and aggressively, sometimes with disastrous outcomes.

This was what happened to RewardMe, a 2010 start-up devoted to the “gamification” of the retail and restaurant industry.

Yu-kai Chou, a gamification guru, came up with the idea of implementing game-like features into customers’ digital loyalty. Like playing a game, customers would be deeply engaged and enticed with rewards to encourage them to stick to a brand.

RewardMe met with astounding initial success, achieving product metrics that were 10 times better than those of its competitors. Chou wasted no time in expanding and deploying the product across the United States.

It caught the attention of brands like Carls Jr and Subway, and was soon closing million dollar deals with huge chains.

Chou had a passionate team that worked 100-hour weeks on a low salary hoping to win big. However, the cracks started to reveal themselves, as the business was not sufficiently funded to deliver on its promises.

Failing to get the much needed VC investments, the company eventually stalled in offering their products to the more than 40,000 interested parties on the waiting list. Lacking the firm foundation to grow his business and being unable to cope with the pressure, Chou closed the company’s doors in 2012.

#6 Metao – Burning through the cash pile

We come to the final and most hard-hitting reality that businesses must face – running out of cash.

The downfall of one of China’s most well-funded e-commerce platforms is a cautionary reminder of the importance of maintaining a healthy cash flow. Metao was founded by Xie Wenbin who decided to start his business after witnessing a boom in the industry in China.

The company saw initial success as it raised US$30mil in 2014. Its active users numbered in the millions, bringing in huge sales figures.

Metao succeeded because it offered low prices for its goods. Things started to change in 2015, when the industry grew more overcrowded, with competitive players like Tmall, JD and Alibaba pushing the company into an aggressive price war.

This was costly for Xie whose smaller company could not outbid its more well-funded counterparts.

Taking a huge hit to its revenues, they suffered additional losses after several wrong turns. It made a huge shift by focusing on South Korean products – which limited its customer base. It also moved its headquarters to a larger, more expensive home in Beijing.

By 2016, employees were jumping ship in droves as they sensed the declining financial situation in Metao. Xie had to give up most of its non-profitable departments and then laid off large numbers of employees.

The finishing line

Like a floating iceberg, the cautionary tales of the 90% that fail are often buried under the glitz of entrepreneurs who win big. Nevertheless, it is crucial for aspiring founders to learn why many failed to make the cut to avoid the common pitfalls.

This article first appeared on Leaderonomics.com